[ad_1]

A person in drug addiction recovery looks on from a substance abuse treatment center in Westborough, Massachusetts. John Moore/Getty Images hide caption

toggle subtitle

John Moore/Getty Images

A person in drug addiction recovery looks on from a substance abuse treatment center in Westborough, Massachusetts.

John Moore/Getty Images

Federal data released last week showed that more than 101,000 Americans died of drug overdoses in a one-year period. This was due in part to the pandemic and treatment interruptions, as well as an increase in the use of methamphetamine and fentanyl.

But there is positive news. A recent study on recovery success, co-authored by Dr. David Eddie, shows that three out of four people with addiction recover if they get the care they need.

In participating regions, you’ll also hear a local news segment to help you understand what’s happening in your community.

Email us at considerthis@npr.org.

This episode was produced by Mallory Yu, Brent Baughman, Chad Campbell and Sean Saldana. It was edited by Ashley Brown and Andrea de Leon. Our executive producer is Cara Tallo.

[ad_2]

Source: Consider this from NPR: NPRMethadone Clinic Near Me – Methadone Clinic NYC – Methadone Clinics USA

[ad_1]

Nicotine is addictive because it activates the brain’s dopamine network, which makes us feel good. UC Berkeley researchers now show in experiments with mice that high-dose nicotine also activates a recently discovered dopamine network that responds to unpleasant stimuli. This aversive dopamine network could be harnessed to create a therapy that increases the negative effects and decreases the rewards of nicotine. (Image credit: Christine Liu, UC Berkeley)

If you remember your first hit of a cigarette, you know how sickening nicotine can be. However, for many people, the benefits of nicotine outweigh the negative effects of high doses.

Researchers at the University of California, Berkeley have now mapped part of the brain network responsible for the negative consequences of nicotine, opening the door to interventions that could increase aversive effects to help people quit smoking.

While most addictive drugs at high doses can cause physiological symptoms leading to unconsciousness or even death, nicotine is unique in making people physically ill when inhaled or ingested in large quantities. amounts As a result, nicotine overdoses are rare, although the advent of e-cigarettes has made “nic sickness” symptoms such as nausea and vomiting, dizziness, rapid heartbeat and headaches more common.

The new research, conducted in mice, suggests that this aversive network could be manipulated to treat nicotine addiction.

“Decades of research have focused on understanding how nicotine reward leads to drug addiction and what the underlying brain circuits are. In contrast, the brain circuits that mediate the aversive effects of nicotine are largely understudied,” said Stephan Lammel, associate professor of molecular and cell biology at UC Berkeley. “What we found is that the brain circuits that are activated after a high aversive dose are actually different from those that are activated when nicotine is delivered at low doses. Now that we have an understanding of the different brain circuits, we think perhaps we can develop a drug so that when nicotine is taken at low doses, these brain circuits can be co-activated to induce an acute aversive effect. This could be a very effective treatment for nicotine addiction in the future, which currently does not we have”.

Lammel and Christine Liu, who recently earned her Ph.D. of UC Berkeley, also found that nicotine receptors in the reward pathway are desensitized by high doses of nicotine, which likely contributes to the negative experience of high doses.

“Inhibitory inputs and desensitization of nicotine receptors on the same dopamine neurons contribute to decreased dopamine signaling in the reward pathway, and then to decreased feelings of pleasure and thus to behavioral aversion,” Liu said.

Lammel, Liu, graduate student Amanda Tose and their colleagues described the brain circuits involved in nicotine aversion in a paper accepted by the journal Neuron and now published online.

The yin and yang of dopamine

Nicotine, like cocaine and heroin, is known to cause addiction by activating the body’s reward network: nicotine binds to receptors on cells that release the neurotransmitter dopamine in the brain, where it affects everything from pain perception and mood to memory. The dopamine network generally provides positive feedback that reinforces our desire to seek out pleasurable activities.

Christine Liu and Yichen Zhu in Stephan Lammel’s lab at UC Berkeley. Liu, now a postdoctoral fellow, was one of the leaders of the nicotine research. Zhu attended as an undergraduate researcher. (Photo courtesy of Christine Liu, UC Berkeley)

But three years ago, Lammel and his colleagues discovered a parallel dopamine network that responds to unpleasant stimuli by releasing dopamine in different areas of the brain than the dopamine reward network. The discovery of this yin-yang nature of dopamine came at a time when it became clear that dopamine performs quite different functions in various areas of the brain, exemplified by its role in voluntary movement, which is seen affected in Parkinson’s disease.

Lammel’s team has since found that some chemicals also stimulate the negative dopamine network. Lammel, Liu and Tose looked closely at nicotine’s effects on the body precisely because of its known aversive effects at high doses, and found that it also activates the network.

“This subcircuit we reported had a major impact on the field,” Lammel said. “For the first time, we identified this particular subcircuit of the dopamine system that was activated by negative emotional stimuli, such as a burst of electric shock. Now, we have discovered that an entirely different stimulus, a pharmacological stimulus, a drug, activates the same system. This means that the system is specially designed to be activated by aversive stimuli.”

To demonstrate this for nicotine, Liu and his colleagues infused mice with the drug and measured second-by-second dopamine release in the brain using a newly developed technique called dLight-based fiber photometry. Previously, dopamine could only be measured over periods of minutes, obscuring the neurons’ short-term responses to dopamine.

They then used chemical antagonists to inactivate a specific nicotine receptor called alpha-7 in the aversion network, which reduced the effects of aversive nicotine on neuronal activity. Subsequent optogenetic experiments eliminated the aversive behavior.

“In animals where we were able to silence this population of neurons, we actually saw a strong preference for high-dose nicotine,” Liu said. “So by silencing the circuit, we were able to show with certainty that this was a very important neural encoder of the behavioral aspect of high-dose nicotine.”

The only drug designed to help with nicotine cessation, varenicline, might work by increasing aversion via the alpha-7 receptor and decreasing desensitization at the alpha-4/beta-2 receptor, he said, but that’s currently unknown. its precise mechanism of action.

Lammel noted that drugs that block the alpha-7 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor might not work as a treatment for tobacco or nicotine addiction because they would block many necessary functions of the receptor. But identifying this nicotine receptor as key to mammals’ aversion to high-dose nicotine will help researchers develop targeted drugs to adjust the body’s response to a typical dose a smoker would ingest when lighting a cigarette.

“Maybe in the future it will be an approach for nicotine addiction therapy, where we use gene editing technologies to selectively target these receptors in specific brain circuits and then overexpress or eliminate receptors,” said Lammel. “What we provide here is a blueprint of a brain circuit and nicotine receptor subtype that is critically important for the aversive properties of nicotine.”

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (1R01DA042889), the California Tobacco-Related Disease Research Program (26IP-0035), the One Mind Foundation (047483), the Foundation for Research in brain (BRFSG-2015-7) and Wayne and Gladys Valley Foundation. Liu, now a postdoctoral fellow at UC San Francisco, was a Gilliam Fellow at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and an NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Program (GRFP) Fellow. Tose was an NSF GRFP fellow.

Other co-authors of the paper are Jeroen Verharen, Yichen Zhu, Lilly Tang, Johannes de Jong and Jessica Du of UC Berkeley and Kevin Beier of UC Irvine. All Berkeley researchers are members of the Helen Wills Neuroscience Institute on campus.

RELATED INFORMATION

[ad_2]

Source: The secret behind ‘nic disease’ could help break smoking addictionMethadone Clinic In My Area – Methadone Clinics NYC – Methadone Clinics USA

[ad_1]

The increase in opioid deaths in black communities can be linked to health disparities.

The opioid epidemic caused half a million deaths between 1999 and 2019. But far from abating, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a dramatic increase, with more people dying from opioids each year past than in any previous year. However, the contours of the crisis have changed.

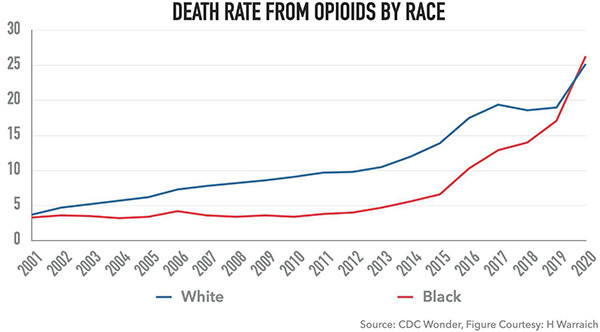

The opioid epidemic has traditionally been thought to primarily affect white Americans, and largely in rural areas. This was partly intentional, as drug companies targeted these areas to avoid the glare of law enforcement. Another reason white Americans were more likely to be addicted to opioids was because blacks were far less likely to receive opioids for pain control, even when medically indicated for emergent conditions. However, new data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) shows that the reason the opioid epidemic is growing at a breakneck pace is because of its rapid infiltration into black communities.

New research shows more black Americans are dying from overdoses

A recently released CDC report offers a stark look at how the opioid epidemic is increasingly trapping black people in its wake. In 2020, opioid overdoses increased by 30% compared to 2019, resulting in 91,799 deaths. However, the increase was not noticed uniformly. The death rate among black Americans increased by 44%, the largest increase among all racial and ethnic groups, and double that for white Americans.

Black youth ages 15-24 saw an 86% increase in the opioid death rate. In fact, according to my analysis of the CDC WONDER database, in 2020 black Americans had a higher opioid death rate than white Americans for the first time in the entire two-decade history of the opioid crisis.

In 2020, for the first time during the entire opioid epidemic, the opioid overdose death rate was higher for black Americans than for white Americans, largely due to the increase in illicit fentanyl. |

Opioid deaths add to the systemic burdens of black communities

One of the black victims of opioid addiction was George Floyd. “Our story, it’s a classic story of how many people become addicted to opioids,” Courteney Ross, Floyd’s girlfriend, testified during the trial in Minneapolis. “We both struggled with chronic pain. Mine was in my neck and his was in my back.” In fact, opioids could have killed George Floyd before his murder in May 2020; he was hospitalized for an opioid overdose in March of that year.

At a time when black communities are suffering disproportionately from the COVID-19 pandemic and police brutality, they are also being doubly harmed by the ongoing opioid epidemic. Opioid epidemic is exacerbating existing inequalities in America: CDC study shows that areas with the highest degree of income inequality had double the opioid death rate among black Americans in compared to the areas with the lowest income inequality.

What is causing this increase in opioid deaths?

Why has opioid misuse increased among black Americans during the pandemic? A key culprit is the rise of fentanyl, an opioid that is far more lethal than others, which has invaded America through rampant exports from overseas. Research my team published in JAMA showed that the pandemic was associated with a drop in prescriptions for opioids, and subsequent work suggested that this occurred only for new users rather than opiates which had previously been prescribed.

This reduction was due to the closing of clinics and pharmacies, but stopping prescription opioids abruptly can be dangerous. A recent study showed that patients who are suddenly stopped from opioids are at increased risk of suicide, as it can lead them to turn to illicit opioids such as heroin and fentanyl.

Unequal access to addiction treatment adds to the problem

One of the main reasons for the growing racial divide on opioids is based on who actually has access to substance use treatment. While only 14% of those who died from opioids received substance abuse treatment overall, among black Americans the proportion was 8%, the lowest of any group. Treatment services for opioid use disorder were severely affected by the pandemic, leading to abrupt closures of services that served as lifelines for many users.

Policy changes and better access to pain treatments could turn the tide

Simply making substance use and mental health resources available is unlikely to move the needle on its own. Opioid death rates among black Americans were highest in areas with the greatest availability of mental health and addiction treatment centers. What is really needed is a broad public health and outreach campaign in Black communities that highlights the dangers of opioid misuse, provides community resources for harm reduction and addiction treatment, and reduces stigma associated with opioid misuse and seeking treatment.

One of its creators revealed that the war on drugs was racist in nature. The last thing we need is for us to re-criminalize the use and misuse of these drugs, which could put already vulnerable black communities disproportionately affected by opioids and overzealous law enforcement in double jeopardy . Getting fentanyl off the streets through stricter scrutiny is an important part of the national drug control strategy released earlier this year by the Biden administration, but care must also be taken to ensure that the black Americans who are in pain or have been prescribed a chronic illness. opioids, they don’t let themselves suffer.

Evidence-based interdisciplinary pain treatments can provide significant relief for people with chronic pain, and an important goal should be to ensure that all patients, especially those who already suffer disproportionately, receive access to these therapies. However, to ensure that black people are able to obtain adequate pain relief and are also not disproportionately affected by the opioid epidemic, we must ensure that barriers to treatment are removed once and for all.

[ad_2]

Source: Opioid addiction and overdoses are increasingly harming black communitiesMethadone Clinic Near Me – Methadone Clinics New York – Methadone Clinics USA